When you reach 50, you start to notice friends either getting sick, dying, being diagnosed, or ramping up the fitness routine because, well nigh is near. There are some great stories of survival in my life, and some not so. Now at 60, my health is mostly sorted, though it has taken longer than expected. I’m alive.

My life has been shaped by repeated loss. Early on, I asked whether this was my path ie to understand grief. The answer I got was more of the same, so I’m going to assume yes and start writing about it. Writing is a release for me, plus the lived experience may help someone else.

In my experience, grief moves in ten-year cycles. We get through the immediate pain at varying rates and circumstances, but the residual effects take far longer to surface and resolve.

Well before my twin died when we were 35 by freak accident (I’ve captured my trauma, here), my understanding of grief had already started. In fact, it began when I was nine. My parents had separated, and my mother was involved in a horrific motor vehicle accident that left her permanently scarred. At that age and time in the 70’s, we didn’t yet have a language for grief but we did have a resolve of stiff upper lip and carry on.

Mum was away recovering for three months after the accident. Only later did I understand the double impact when my twin died: he had been my anchor through the separation anxiety I carried after my mother left, and losing him meant losing my primary coping mechanism as well.

She came back to Dad and family after the accident, and life throughout the rest of my childhood was relatively normal, as far as I could tell and remember.

Fast forward: Mum went away again for six months after my twin died, when I was 35, after she attempted suicide. The grief of losing her only son was too much to bear. She was institutionalised, and we weren’t allowed access to see her initially. When she came out, she was still broken. She did eventually try again, unsuccessfully. I stood at the end of her hospital bed that second time and said, “I’m sorry I’m all you have left, but I need you. Please don’t do this again.”

I recognise now that it was an act of selfishness. I didn’t know better or how to deal with my own grief, or what I would do if I lost her as well. I was at breaking point.

She passed in old age though, almost in peace. She died of gallbladder cancer after a long residency in aged care. The 10 years leading to mum’s last days is when I became family carer, power of attorney, go to, run around, and main support person. I loved being her family carer as I got to spend some pretty amazing moments with her. I’ve documented my family carer journey as some of it was overwhelming but it was great making her smile when we championed dignity in care together. After her passing, it felt as if my identity, purpose and best friend went too. I’m only 5 years in to this round of grief… so excuse me for not dwelling.

My second marriage had already faltered long before mum’s passing… in fact it was soon after my twin died. Obviously all my fault. I mean, tricky family situation to deal with hey.

By comparison, my first marriage separation was quite amicable. It wasn’t until I lost custody of my daughter that the ‘amicable’ stopped. My second husband essentially started and ended a relationship with me in a mess. At least the middle part was good.

Both marriages gave me my greatest joys: my daughters. The paradox of motherhood, though, is learning to let go and to find peace in that. Because of early loss and lifelong separation anxiety, this requires a daily emotional check-in. That reality has been brought into sharp focus as one daughter lives overseas, and the other navigates a full life while carrying the residual impact of childhood trauma shaped, in part, by circumstances I created during the custody battle.

Grief. It comes in many forms.

Loss of a loved one is top of the pops, but custody, separation, loss of home, routine, purpose, friendships and employment are all emotional. I’ve experienced them all.

Lived experience of grief has a new meaning. It’s my life.

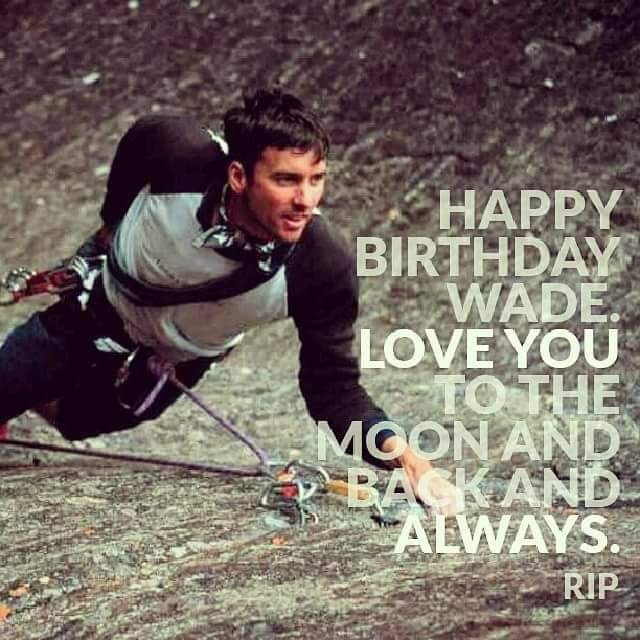

Friendships come and go. They say for a season or reason. Some movement has been easy, others not so. When your friend of 30 years is found dead in his unit, and then another passes after a short aggressive stint with cancer, you start to track your own health progress and catch yourself on the flipside of mental health check ins. You appreciate how short a lifespan can be.

I knew from 35 we weren’t all destined to ‘live forever’, however it brings it closer to home when friends start dying.

There’s more. It will come as no surprise through all this, that I’ve had two further major relationships. The third never progressed beyond an engagement, but its ending devastated me. I spiralled, deflecting energy into busyness instead of resolving my own patterns. After a series of short, hopeless flings, I entered a third marriage that was never right. There is relief now that it’s over. I can finally focus on myself and sorting through my patterns of emotional heartache. That resolve comes from maturity — and exhaustion from not recognising patterns sooner. (I’ve written about this, here)

Turning 60, I choose joy, light, and happiness. My #happyspan

That choice comes with acceptance of a life shaped by grief, and with moments where I still feel overwhelmed and unsure how to express it, or to whom.

It has been a complex life but I’m ready for my third chapter.

“Life is short, live it. Love is rare, grab it. Anger is bad, dump it. Fear is awful, face it. Memories are sweet, cherish it.” – Unknown

Three lessons in summary

Lesson one: Grief is not an event. It’s a system you live inside.

Grief didn’t arrive once and leave. It embedded early, long before the headline losses. Parental separation. Maternal absence through trauma. The loss of my twin later didn’t start the story; it exposed the architecture underneath it. Over time, I learned that grief operates in cycles, often a decade long, resurfacing as identity loss, anxiety, or emotional exhaustion rather than raw pain.

The key insight: you don’t “move on” from grief. You build capability to operate alongside it.

Lesson two: Coping mechanisms work until they don’t.

My twin, marriages, caregiving, busyness, responsibility, even romantic attachment all functioned as stabilising structures at different points. They kept me upright. They also became load-bearing. When each collapsed, the impact was disproportionate because they were doing more than they were designed to do.

The hard-earned lesson is that survival strategies are time-bound. If they’re not reviewed, they eventually become liabilities rather than assets.

Lesson three: Accountability without self-erasure is the only way forward.

I’ve named where my pain spilled into relationships, where decisions shaped outcomes for others, including my children. But I’ve stopped turning accountability into a personal prosecution. That shift matters.

Responsibility isn’t about endless self-blame; it’s about pattern recognition, repair where possible, and refusing to keep paying for the same lesson twice. This is where maturity shows up.

It’s not a perfect life, but insights carry us forward.

Charlie would love to start the conversation with you…